The Beautiful Icons

I believe that Art should sanctify Nature; I believe that Vision without Spirit is futile; and the mission of the aesthete is to erect things of beauty as imperishable icons.

I believe that Art should sanctify Nature; I believe that Vision without Spirit is futile; and the mission of the aesthete is to erect things of beauty as imperishable icons. From the age of fourteen, Maurice Denis recorded in his Journal his ardent desire to be a Christian painter. At the Lycée, he met Vuillard and Roussel, and at the Académie Julian, he became friends with Bonnard, Ranson and Sérusier. These young artists, who shared the same ideas about creating a synthetist, idealistic kind of art, founded the group called the Nabis, from a Hebrew word meaning “prophet.” Their aim was to render in comprehensible signs the inexpressible ideal, the secret language of God, of love and emotion. Denis, dubbed “the Nabi of the beautiful icons,” became their spokesman and theorist. His striking Easter Procession, a mystical symbolist painting, shows “figures of the soul” wandering along the “path of life” in search of their vocation, through the wavering blue shadows of a sacred grove. In the distance, nuns kneel before an angel who is guiding them along the way toward their calling.

The Poetic Arabesques of Art Nouveau

To start with, the pure arabesque, as plain as possible; a wall is empty: fill it with symmetrical brushstrokes of shapes in harmonious colours (stained glass, Egyptian paintings, Byzantine mosaics, Japanese wall hangings).

To start with, the pure arabesque, as plain as possible; a wall is empty: fill it with symmetrical brushstrokes of shapes in harmonious colours (stained glass, Egyptian paintings, Byzantine mosaics, Japanese wall hangings).

Anticipating Art Nouveau, Denis wanted to rethink the interior decoration of the “modern house.” Ladder in the Foliage, designed for a ceiling, was the first of many large-scale decorative paintings. He also created patterns for wallpaper and designs for stained glass, tapestries and ceramics. Posters, books, fans and even blinds became vehicles for incorporating art into everyday life, transcending the distinction between architecture, writing and painting.

The Nabi Avant-garde

Remember that a picture – before being a war horse or a nude woman or an anecdote of some sort – is essentially a flat surface covered with colours assembled in a certain order.

Remember that a picture – before being a war horse or a nude woman or an anecdote of some sort – is essentially a flat surface covered with colours assembled in a certain order.

Together with his fellow Nabis, Denis opened up a new direction for Post-Impressionist modernism, taking his inspiration from the painting of Gauguin and Van Gogh and making the picture, rather than the subject, the priority. The maxims of this bold new generation were violent colours, simplified shapes and emphasis on line – an approach that Matisse and the Fauves would embrace, too. Denis, even more than Bonnard or Vuillard, took his famous precept to the limit in his small paintings, often executed on simple pieces of cardboard, as in this Sunlight on the Terrace. With its emphatically decorative impact, this little experimental landscape, now famous, is really a covert flirtation with the abstract.

For Love of Marthe

Our two souls leaned towards each other in a slow movement. I was sad that I could not weep; she was so infinitely beautiful. Mysteries were being celebrated in the velvet depths of her eyes, and I was unworthy to witness them.

Our two souls leaned towards each other in a slow movement. I was sad that I could not weep; she was so infinitely beautiful. Mysteries were being celebrated in the velvet depths of her eyes, and I was unworthy to witness them.

The gentle, affectionate Marthe, the artist’s wife and muse, was to give him seven children and the joy of family life. His art, inspired by love, portrayed her as the Wise Virgin in a Garden, the Princess in a Tower, the Woman Asleep in the Enchanted Forest, the triumphant Mother and the Italian Madonna. Marthe at the Piano is a young man’s declaration of love to his sweetheart, symbolized by a bouquet. They had the same tastes in music (Marthe was a gifted musician) and in avant-garde literature and theatre – the reference here is to the playwright Maeterlinck. Their friends included the composers Debussy, Chausson and Vincent d’Indy and writers Mallarmé, Valéry, Gide and Claudel.

Italy and the “Return to Order”

The classical methods, which best display the artist’s good faith and commitment by ennobling them, nevertheless tend to diminish the expression of his own emotions and personal taste. His originality is obscured and, as it were, disappears in the breadth and perfection of the formula.

The classical methods, which best display the artist’s good faith and commitment by ennobling them, nevertheless tend to diminish the expression of his own emotions and personal taste. His originality is obscured and, as it were, disappears in the breadth and perfection of the formula.

In 1898, Denis’s friend André Gide had shown him the beauties of Rome. The artist had previously illustrated Gide’s Le voyage d’Urien, an indispensable book for contemporary bibliophiles (our exhibition shows several of the little-known drawings for this book). Convinced that the way forward for modern art was to return to classical order, from this period onwards Denis sought to impose on his work a new concern for order and discipline. A whole generation was to follow his lead in seeking new solutions, including Picasso in the postwar period and Le Corbusier in La leçon de Rome. Henceforth, Denis continued to revisit Italy, still his favourite destination despite many other trips abroad, including a few days (and three lectures ) in Canada in 1927.

A Time of Harmony

At Perros, Silencio. It is striking how appropriate the house is to my life, made up as it is of my children, painting, the beach and my studio. And then there are the woods, and lastly solitude, and the most beautiful sunsets.

At Perros, Silencio. It is striking how appropriate the house is to my life, made up as it is of my children, painting, the beach and my studio. And then there are the woods, and lastly solitude, and the most beautiful sunsets.

Brittany, a traditional region that inspired many French primitivist artists, was Denis’s favourite place for summer vacations. At Silencio, the house in Perros-Guirec that he purchased in 1908, he created an Arcadian existence. September Evening celebrates his daughters playing happily on the beach and Marthe nursing their first son. This very modern seaside holiday scene, bathed in the golden light of sunset, becomes a timeless family idyll.1

Montreal Musem of Art

Montreal Musem of Art

Febrary 22 to May 20 2007

Michal and Renata Hornstein Pavilion

(from top right: denis; toshihide migata; speer;

toshikata mizuno; hanko kajita; kurzweil; toshikata mizuno; keishu takeuchi)

Labels: hanko kajita, keishu takeuchi, maurice denis, max kurzweil, nabi, speer, toshihide migata, toshikata mizuno

while actually reading the text in my copy of 'hidden impressions,' the catalogue for the exhibition of the same name at the MAK in vienna, of instances where the japanese influenced the austrian arts. we'll get back to that catalogue in a future post, but for now, let's follow this little adventure.

while actually reading the text in my copy of 'hidden impressions,' the catalogue for the exhibition of the same name at the MAK in vienna, of instances where the japanese influenced the austrian arts. we'll get back to that catalogue in a future post, but for now, let's follow this little adventure. i was wildly taken with the two images of japanese endpapers, the cranes on the salmon background and the puppies. sure i had seen a western equivilent, i searched for days to no avail. all of the western endpapers, even those from childrens' books, were, to my eyes anyway, far more rigid by design.

i was wildly taken with the two images of japanese endpapers, the cranes on the salmon background and the puppies. sure i had seen a western equivilent, i searched for days to no avail. all of the western endpapers, even those from childrens' books, were, to my eyes anyway, far more rigid by design. refusing to give up, i started perusing some others of my books. i double-checked the catalogue and all of my other books about design in vienna at that time: nothing. why, i asked myself, and still do, have japanese endpapers in the catalogue with no japonisme version for comparison?

refusing to give up, i started perusing some others of my books. i double-checked the catalogue and all of my other books about design in vienna at that time: nothing. why, i asked myself, and still do, have japanese endpapers in the catalogue with no japonisme version for comparison? i started on my other books about paper, wallpaper, and had myself an aha moment. i recalled having noticed so many times how actually un-equivalent these matches-up usually are. rarely does a japanese design form get re-interpreted in some into something comparable back and forth. usually, it, like some inherited traits, skips a generation.

i started on my other books about paper, wallpaper, and had myself an aha moment. i recalled having noticed so many times how actually un-equivalent these matches-up usually are. rarely does a japanese design form get re-interpreted in some into something comparable back and forth. usually, it, like some inherited traits, skips a generation. but once i found these, not only didn't they surprise me, but they gave me deeper understanding in both sides of the equation. first, we've discussed the lesson that the west learned that caused them to question the validity of any differences between art, decoration, and craft.

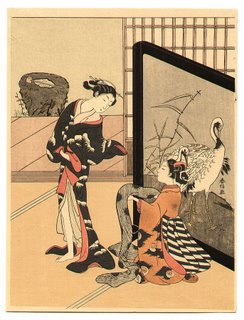

but once i found these, not only didn't they surprise me, but they gave me deeper understanding in both sides of the equation. first, we've discussed the lesson that the west learned that caused them to question the validity of any differences between art, decoration, and craft. no one embraced this concept more strongly than the nabis, for whom there was no less a creative act in creating wallpaper than in painting a painting. much of what we know as paintings are actually bits of a wall-hanging or a screen (see here), but even when the item was a painting itself, it was covered with wallpaper, and, or, the sort of design that hangs in an invisible balance between subject and surround.

no one embraced this concept more strongly than the nabis, for whom there was no less a creative act in creating wallpaper than in painting a painting. much of what we know as paintings are actually bits of a wall-hanging or a screen (see here), but even when the item was a painting itself, it was covered with wallpaper, and, or, the sort of design that hangs in an invisible balance between subject and surround.