the longest day!

Why, who makes much of a miracle?

Why, who makes much of a miracle?As to me I know of

nothing else but miracles,

Whether I walk the streets of Manhattan,

Or dart my sight over the roofs

of houses toward the sky,

Or wade with naked feet along the beach just in the edge of the water,

Or stand under trees in the woods,

Or talk by day with any one I love, or sleep in the bed at night with any one I love,

Or sit at table at dinner with the rest,

Or look at strangers opposite me

Or look at strangers opposite meriding in the car,

Or watch honey-bees busy around the hive of a summer forenoon,

Or animals feeding in the fields,

Or birds, or the wonderfulness

of insects in the air,

Or the wonderfulness of the sundown, or of stars shining so quiet and bright,

Or the exquisite delicate thin curve of the new moon in spring;

These with the rest, one and all, are to me miracles,

The whole referring, yet each distinct and in its place.

To me every hour of the light

To me every hour of the lightand dark is a miracle,

Every cubic inch of space is a miracle,

Every square yard of the surface of the earth is spread with the same,

Every foot of the interior

swarms with the same.

To me the sea is a continual miracle,

To me the sea is a continual miracle,The fishes that swim—the rocks—the motion of the waves—

the ships with men in them,

What stranger miracles are there?

Walt Whitman

Commonplace miracle:

Commonplace miracle:that so many commonplace miracles happen.

An ordinary miracle:

in the dead of night

the barking of invisible dogs.

One miracle out of many:

a small, airy cloud

yet it can block a large and heavy moon.

Several miracles in one:

Several miracles in one:an alder tree reflected in the water,

and that it's backwards left to right

and that it grows there, crown down

and never reaches the bottom,

even though the water is shallow.

An everyday miracle:

winds weak to moderate

turning gusty in storms.

First among equal miracles:

First among equal miracles:cows are cows.

Second to none:

just this orchard

from just that seed.

A miracle without a cape and top hat:

scattering white doves.

A miracle, for what else could you call it:

today the sun rose at three-fourteen

and will set at eight-o-one.

A miracle, less surprising than it should be:

A miracle, less surprising than it should be:even though the hand has fewer

than six fingers,

it still has more than four.

A miracle, just take a look around:

the world is everywhere.

An additional miracle,

as everything is additional:

the unthinkable is thinkable.

Wislawa Szymborska

translated by Joanna Trzeciak

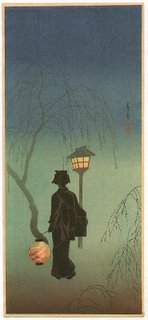

oops... almost forgot

Labels: alvin ailey, dance, edward penfield, marcello dudavich, poetry, rafael de penagos, solstice, torne esquius, vallotton, walt whitman, Wislawa Szymborska