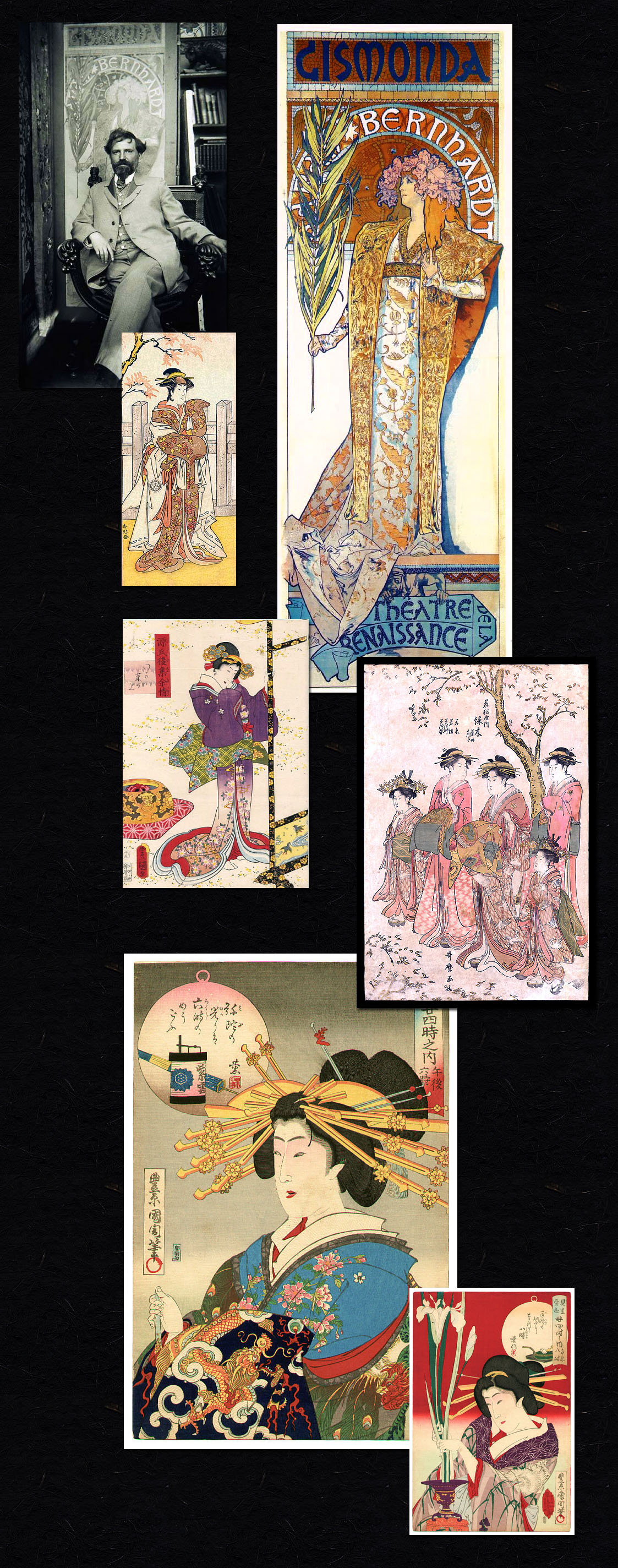

mucha was an unknown. yes, he was making his living by his art, an obscure illustrator, and this was his dream -- well, not the obscure part. one night when he was working late into the night, sarah bernhardt phoned the printer in a fit of pique! this new poster!!, she cried. it will not do! (of course she probably cried this in french)

although it may sound like a scene out of a busby berkeley movie, the only artist they could find that snowey night was this little man, awork at his station. and he vowed he would give it a try.

the rest, as they enjoy repeating, is l'histoire. she loved the poster so much that she signed mucha to be her exclusive poster-maker, and more, her costume and jewelry designer, stage sets, headdress and more. his work was so original! like nothing seen before--not even in mucha's own work!

and it suddenly became the design rage throughout paris: the scroll-like shape, the simplified grace of one woman, adorned, and set off by her glorious fabric. mucha was an overnight success, posters were seen for the first time as fine art, and the definition of art nouveau had now been solidified.

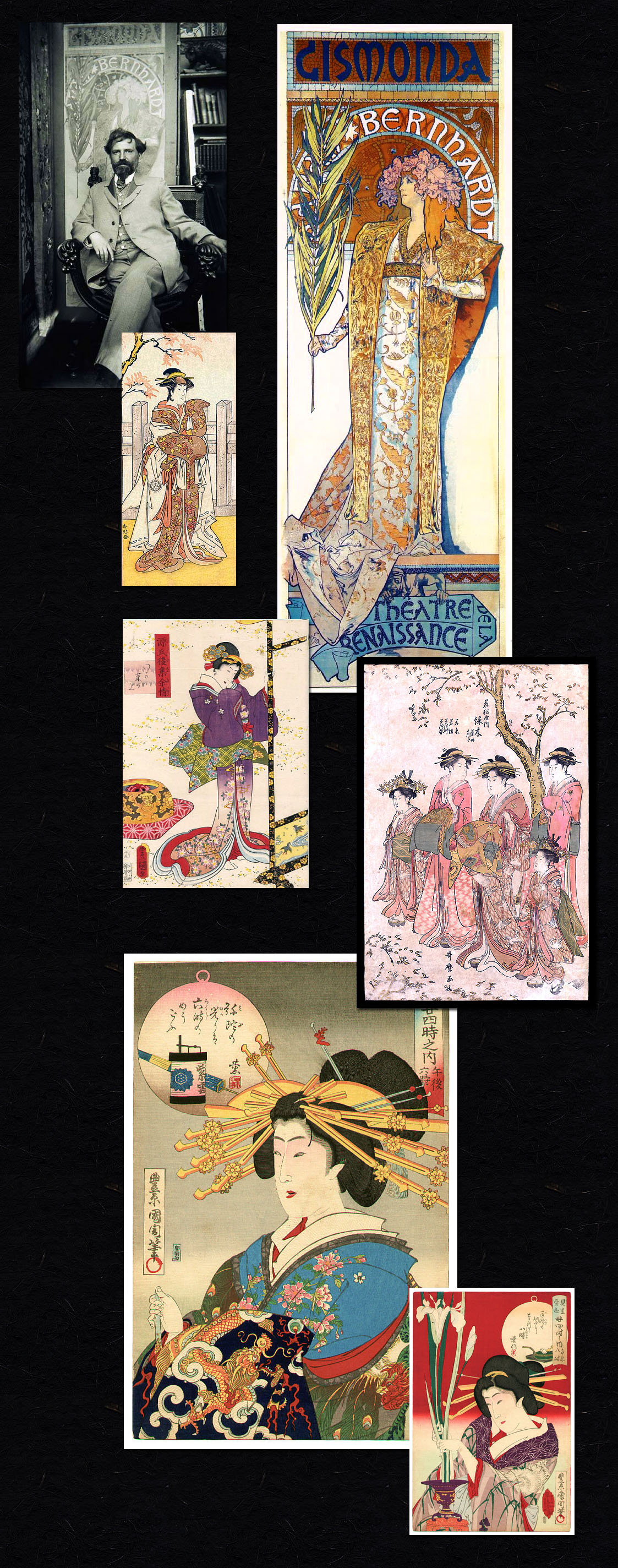

but... uh... wait.... you know what i'm going to say, don't you? gee, wonder where mucha found the inner vision to create something so "revolutionary"? come on now--give it a guess.

the solitary peaceful woman, the flowery hairpiece, the fabric and background as focus, the lack of perspective, even the shape of the dress, the clothing--what mucha did for a decade is to put a slavic/parisian spin on an ancient design scheme and claim it as his own.

and rarely if ever do i see anyone suggest otherwise, though to me it couldn't be more obvious.

(mucha's gismonda poster, his first of this style, is from 1894. the image just below the artist's photo is from about 50 years before that, i believe. forgot to get a credit for that one. below that, kunisada, 1858, in purple. notice her hair ornaments. in pink to the right are courtesans--with the elaborate wooden stick hair ornaments--and maiko, apprentice geisha, with the garland of flowers. sarah's headdress is much more a maiko hairdo than a geisha; yes it is inventive, but not invented. this one is by utamaro kitagawa and dates to the 1700s. and then two from kunichika toyohara from 1890. women of presence clearly did exist in print before mucha reawoke them in a new vernacular.)

please don't get me wrong--i adore mucha's work. i seem to never tire of it. i remember the thrill of seeing the original of one of his posters, a sketch, i guess, at the zimmerli at rutgers, that thin, human pencil line. so simple. it's just that, well, credit where credit's due, don't you think? what do you think?

Labels: alfonse mucha, fashion, Kunichika Toyohara, Kunisada Utagawa, Utamaro Kitagawa, zimmerli

While the long grain is soft- ening

She sits at the foot of the bed.

My mother combs,

But I know

(Li-Young Lee was born in 1957 in Jakarta, Indonesia, of Chinese parents. In 1959, his father, after spending a year as a political prisoner in President Sukarno's jails, fled Indonesia with his family. Between 1959 and 1964 they traveled in Hong Kong, Macau, and Japan, until arriving in America. Rose, the book from which this poem is taken, was published by BOA Editions, Ltd. upper left: utamaro kitagawa; edgar degas; gotosei kunisada; henri-edmond cross; utamaro kitagawa; edgar degas; gotosei kunisada.)