corporations are not people, my friend

THIS IS A PERSON

THIS IS A PERSON

THIS IS A PERSON

THIS IS A PERSON

THESE ARE PEOPLE TOO!

THESE ARE PEOPLE TOO!

Labels: eliza draper gardiner, elyse ashe lord, walter j phillips

THIS IS A PERSON

THIS IS A PERSON

THIS IS A PERSON

THIS IS A PERSON

THESE ARE PEOPLE TOO!

THESE ARE PEOPLE TOO!

Labels: eliza draper gardiner, elyse ashe lord, walter j phillips

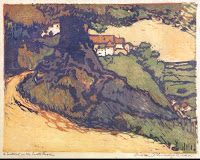

Labels: cuno amiet, ernest watson, grace rhoads dean, gustave baumann, klimt, margaret jordan patterson, walter j phillips

Born in the Czech Republic (then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire) in the mid-nineteenth century to middle-class, German-speaking Jewish parents, Emil Orlik (1870–1932) shares many biographical details with Gustav Mahler. Even so, these similarities could be overlooked as insignificant if it weren’t for the parallel paths that these artists took in later life, which eventually led to a hasty friendship and a mysterious falling-out. Orlik’s father was a respected tailor and the family lived in Prague near (but significantly not in) the Jewish ghetto. Like Mahler’s family, they were proud of their success and hopeful for the future. Orlik would later, like Mahler, also show a fascination with his Jewish heritage, producing lithographs (1897–1904) of everyday life in the Jewish quarter: crumbling buildings, somber bearded men, and the famous ancient Jewish cemeteries (still a must-see for visitors to Prague), with tombstones jutting from the ground like broken teeth.

Born in the Czech Republic (then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire) in the mid-nineteenth century to middle-class, German-speaking Jewish parents, Emil Orlik (1870–1932) shares many biographical details with Gustav Mahler. Even so, these similarities could be overlooked as insignificant if it weren’t for the parallel paths that these artists took in later life, which eventually led to a hasty friendship and a mysterious falling-out. Orlik’s father was a respected tailor and the family lived in Prague near (but significantly not in) the Jewish ghetto. Like Mahler’s family, they were proud of their success and hopeful for the future. Orlik would later, like Mahler, also show a fascination with his Jewish heritage, producing lithographs (1897–1904) of everyday life in the Jewish quarter: crumbling buildings, somber bearded men, and the famous ancient Jewish cemeteries (still a must-see for visitors to Prague), with tombstones jutting from the ground like broken teeth.

Like Mahler, Orlik was confident in his calling as an artist and sure of his ability, but his talent was not immediately realized. In 1889, Orlik obtained permission from his father to study art in Munich; however, he was denied admission to the renowned Academy of Fine Art there, so he enrolled in a private art school. After proving his talent, he was accepted at the Academy, although he soon grew exasperated with the conservatism of the professors and left in 1893 to work in modern, naturalist styles popular at the time. The years at the Academy, however, had sparked an interest in him that would guide his life’s work: printmaking.

Like Mahler, Orlik was confident in his calling as an artist and sure of his ability, but his talent was not immediately realized. In 1889, Orlik obtained permission from his father to study art in Munich; however, he was denied admission to the renowned Academy of Fine Art there, so he enrolled in a private art school. After proving his talent, he was accepted at the Academy, although he soon grew exasperated with the conservatism of the professors and left in 1893 to work in modern, naturalist styles popular at the time. The years at the Academy, however, had sparked an interest in him that would guide his life’s work: printmaking.

During the next few years, he began to develop his career, contributing work to journals such as Jugend (“Youth”) and, in 1897, the prestigious journal Pan, where he published his first woodcuts. The art of the woodcut became a passion for him, and in 1898 he went on his first trip abroad — to England, Scotland, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Paris — where he had the opportunity to see many Japanese color woodblock prints. Japan had opened to the West in 1854 and there had been a steady stream of artifacts from the East since that time. The Impressionists (e.g., Whistler, Monet, Degas, Van Gogh, Cassatt) had embraced Japanese art more than two decades before Orlik discovered it, but trends moved slowly and the German/Austrian artistic tradition was only beginning to feel the waves of the Japanese tsunami that hit Western art at the end of the nineteenth century.

During the next few years, he began to develop his career, contributing work to journals such as Jugend (“Youth”) and, in 1897, the prestigious journal Pan, where he published his first woodcuts. The art of the woodcut became a passion for him, and in 1898 he went on his first trip abroad — to England, Scotland, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Paris — where he had the opportunity to see many Japanese color woodblock prints. Japan had opened to the West in 1854 and there had been a steady stream of artifacts from the East since that time. The Impressionists (e.g., Whistler, Monet, Degas, Van Gogh, Cassatt) had embraced Japanese art more than two decades before Orlik discovered it, but trends moved slowly and the German/Austrian artistic tradition was only beginning to feel the waves of the Japanese tsunami that hit Western art at the end of the nineteenth century.

What Orlik saw in museums and print shops, particularly in Paris, was new and exciting to him. Along with the other artists who formed the Secession in Vienna, he was looking for an utterly new, uncorrupted form. Internationalism also appealed to Secession artists: “We want an art without xenophobia. The art of other nations should stimulate us and show us what we ourselves are; we shall appreciate it, and admire it if it is worth admiring; but imitate it we shall not.” Orlik’s aesthetic held true to this declaration.

What Orlik saw in museums and print shops, particularly in Paris, was new and exciting to him. Along with the other artists who formed the Secession in Vienna, he was looking for an utterly new, uncorrupted form. Internationalism also appealed to Secession artists: “We want an art without xenophobia. The art of other nations should stimulate us and show us what we ourselves are; we shall appreciate it, and admire it if it is worth admiring; but imitate it we shall not.” Orlik’s aesthetic held true to this declaration.

In 1899, Orlik became a member of the Viennese Secession and began showing works in that city, and in February 1900 the Secessionists exhibited a collection of Japanese art, which gave Orlik a “foretaste” of the trip he would soon take. Japanese art had, by this point, been taken up wholeheartedly by Secession artists, as evidenced by Gustav Klimt’s vertical compositions and use of gold leaf and print patterns, Oskar Kokoschka’s interest in Japanese fans, and Carl Moll’s use of woodcut and simplified landscape. ... Given the Mahlers’ place in Viennese high society, it seemed almost inevitable that they should come to know Emil Orlik, but this acquaintance would have to wait, as Orlik was headed off on a two-year trip to Japan (1900–1901).

In 1899, Orlik became a member of the Viennese Secession and began showing works in that city, and in February 1900 the Secessionists exhibited a collection of Japanese art, which gave Orlik a “foretaste” of the trip he would soon take. Japanese art had, by this point, been taken up wholeheartedly by Secession artists, as evidenced by Gustav Klimt’s vertical compositions and use of gold leaf and print patterns, Oskar Kokoschka’s interest in Japanese fans, and Carl Moll’s use of woodcut and simplified landscape. ... Given the Mahlers’ place in Viennese high society, it seemed almost inevitable that they should come to know Emil Orlik, but this acquaintance would have to wait, as Orlik was headed off on a two-year trip to Japan (1900–1901).

The purpose of this trip, aside from satisfying a Wanderlust he seemed to retain throughout life, was to learn the actual techniques of Japanese color woodblock printing from the source. Concerned that artists of the Jugendstil may have “gotten it wrong,” he sought an authenticity of style, subject, and technique that other Secession and Impressionist artists seemed to disregard. Known as a friendly extrovert, he seems to have met and studied with many of the Japanese practitioners at the time. In this remarkable period, the Japanese were as avidly interested in the West as Westerners were keen on Japan. Japanese journalists published some of Orlik’s prints in their newspapers at the same time that Orlik was collecting original Japanese artwork to bring back to Europe. After returning from this trip, Orlik published a collection, Aus Japan (1904), and also showed sixteen works at the 13th Viennese Secession Exhibit.

The purpose of this trip, aside from satisfying a Wanderlust he seemed to retain throughout life, was to learn the actual techniques of Japanese color woodblock printing from the source. Concerned that artists of the Jugendstil may have “gotten it wrong,” he sought an authenticity of style, subject, and technique that other Secession and Impressionist artists seemed to disregard. Known as a friendly extrovert, he seems to have met and studied with many of the Japanese practitioners at the time. In this remarkable period, the Japanese were as avidly interested in the West as Westerners were keen on Japan. Japanese journalists published some of Orlik’s prints in their newspapers at the same time that Orlik was collecting original Japanese artwork to bring back to Europe. After returning from this trip, Orlik published a collection, Aus Japan (1904), and also showed sixteen works at the 13th Viennese Secession Exhibit.

It was after his return from Japan that Orlik first met Mahler. The Czech conductor Josef Stransky remembered a meeting between Mahler and Orlik in a cafe in Prague:

It was after his return from Japan that Orlik first met Mahler. The Czech conductor Josef Stransky remembered a meeting between Mahler and Orlik in a cafe in Prague:

Stransky assumed that this encounter in 1904 was the first meeting between the two, but now it appears, according to Henry-Louis de La Grange, that Mahler and Orlik already knew each other. The famous charcoal drawing and the etching date from 1902 and 1903, respectively. Orlik also encountered Mahler at an April 14, 1902, gala for the Secession’s Beethoven Exhibition, where Mahler conducted a choral passage from Beethoven’s Ninth (“Ihr sturzt nieder, Millionen?”), transcribed for six trombones. Like Klinger’s sculpture and Klimt’s frieze, Mahler’s refashioning of Beethoven was a liberal interpretation; however much traditionalists may have winced to behold this spectacle, the artists were upholding their motto: “Down with borrowed styles,” which resonates with Mahler’s own epithet “Tradition is slovenly.” At a banquet in honor of Max Klinger that night, “There were numerous speeches, and Emil Orlik, recently returned from Japan, gave a toast in spoof Japanese.”

Stransky assumed that this encounter in 1904 was the first meeting between the two, but now it appears, according to Henry-Louis de La Grange, that Mahler and Orlik already knew each other. The famous charcoal drawing and the etching date from 1902 and 1903, respectively. Orlik also encountered Mahler at an April 14, 1902, gala for the Secession’s Beethoven Exhibition, where Mahler conducted a choral passage from Beethoven’s Ninth (“Ihr sturzt nieder, Millionen?”), transcribed for six trombones. Like Klinger’s sculpture and Klimt’s frieze, Mahler’s refashioning of Beethoven was a liberal interpretation; however much traditionalists may have winced to behold this spectacle, the artists were upholding their motto: “Down with borrowed styles,” which resonates with Mahler’s own epithet “Tradition is slovenly.” At a banquet in honor of Max Klinger that night, “There were numerous speeches, and Emil Orlik, recently returned from Japan, gave a toast in spoof Japanese.”

Orlik’s portraits of Mahler are the finest that exist of the composer, and are really exemplary by any standard. Although Orlik never used a “true” Japanese style (he retained central perspective, for instance), he effectively chose aspects of Japanese design to incorporate in his work. One critic remarked of Orlik’s exhibit, “He is today the most Japanese European. But he is still European.” Orlik’s skillful use of Eastern techniques is evidenced by the simple, elegant lines indicating Mahler’s upper body in the etching. The graceful linear motion complements the meticulous detail of the face. In addition, in the charcoal drawing Orlik uses a calligraphic pen-and-ink style to lend the portrait a fluidity that evokes the momentum and force of Mahler’s personality.

Orlik’s portraits of Mahler are the finest that exist of the composer, and are really exemplary by any standard. Although Orlik never used a “true” Japanese style (he retained central perspective, for instance), he effectively chose aspects of Japanese design to incorporate in his work. One critic remarked of Orlik’s exhibit, “He is today the most Japanese European. But he is still European.” Orlik’s skillful use of Eastern techniques is evidenced by the simple, elegant lines indicating Mahler’s upper body in the etching. The graceful linear motion complements the meticulous detail of the face. In addition, in the charcoal drawing Orlik uses a calligraphic pen-and-ink style to lend the portrait a fluidity that evokes the momentum and force of Mahler’s personality.

For some reason that I have been unable to discover, relations soon soured between Mahler and Orlik. One year after their meeting in the Prague cafe, Mahler wrote a letter to Alma indicating that his enthusiasm for Orlik had waned. Alma picked up on the shift in emotion, as in this letter to Mahler:

For some reason that I have been unable to discover, relations soon soured between Mahler and Orlik. One year after their meeting in the Prague cafe, Mahler wrote a letter to Alma indicating that his enthusiasm for Orlik had waned. Alma picked up on the shift in emotion, as in this letter to Mahler:

It will take more research to discover or even speculate about the reason for this sudden and drastic shift in relations between Orlik and the Mahlers. Certainly they ran in similar circuits in society and shared similar interests: the theater (Orlik later designed costumes and sets in Berlin) and the Far East. Mahler’s own fascination with Eastern philosophy and music, which produced Das Lied von der Erde, are rooted firmly in this period around 1900–1902, in which the influence of Asian art and music was flourishing in the trend-setting circles of Viennese artistic elites. Orlik, one of the first Western artists to actually visit Japan, was very important in contributing to the dialogue about Japanese art and how it could and should be incorporated into the “new style” that was being born in the salons and coffeehouses of Vienna.

It will take more research to discover or even speculate about the reason for this sudden and drastic shift in relations between Orlik and the Mahlers. Certainly they ran in similar circuits in society and shared similar interests: the theater (Orlik later designed costumes and sets in Berlin) and the Far East. Mahler’s own fascination with Eastern philosophy and music, which produced Das Lied von der Erde, are rooted firmly in this period around 1900–1902, in which the influence of Asian art and music was flourishing in the trend-setting circles of Viennese artistic elites. Orlik, one of the first Western artists to actually visit Japan, was very important in contributing to the dialogue about Japanese art and how it could and should be incorporated into the “new style” that was being born in the salons and coffeehouses of Vienna.

Emil Orlik moved to Berlin in 1904 and took a post as head of the graphic art and book illustration department at the Academy of the Museum of Applied Arts. He remained there until his retirement in 1930, teaching such artists as George Grosz. In 1917, Orlik was chosen to be the only artist to document the peace talks at Brest-Litovsk. His last overseas trip in 1923 was, like Mahler’s, to New York City, which he said was harder to get used to than China. Orlik died of a heart attack in 1932, just as the Nazis were intensifying their murderous campaign against the Jews in Europe. All but one member of Orlik’s extended family perished. Despite this tragedy, however, his art remains to tell the extraordinary story — often overshadowed by the dark clouds that soon would oppress the twentieth century — of a time when “xenophobia in art” was denounced, exciting information about the world was becoming available, and a new century was unfolding in a spirit of curiosity and creativity, exploration and experimentation.

Emil Orlik moved to Berlin in 1904 and took a post as head of the graphic art and book illustration department at the Academy of the Museum of Applied Arts. He remained there until his retirement in 1930, teaching such artists as George Grosz. In 1917, Orlik was chosen to be the only artist to document the peace talks at Brest-Litovsk. His last overseas trip in 1923 was, like Mahler’s, to New York City, which he said was harder to get used to than China. Orlik died of a heart attack in 1932, just as the Nazis were intensifying their murderous campaign against the Jews in Europe. All but one member of Orlik’s extended family perished. Despite this tragedy, however, his art remains to tell the extraordinary story — often overshadowed by the dark clouds that soon would oppress the twentieth century — of a time when “xenophobia in art” was denounced, exciting information about the world was becoming available, and a new century was unfolding in a spirit of curiosity and creativity, exploration and experimentation.

Labels: emil orlik, gustav mahler